The Seen & The Self Online #1 : From Camgirls to Influencers

The ritual of digital intimacy

Picture this: A young woman is casually chatting, giving a small tour of her apartment, showing you her hedgehog (or trying to … hedgehogs are nocturnal, after all). It’s unremarkable, everyday stuff. Except, thousands of strangers are watching her do it, live.

In the late 1990s, this scenario was a cultural phenomenon. And this girl wasn’t a reality TV contestant or a Hollywood celebrity, but a college student broadcasting her life on the internet 24/7.

Making hummus, showing her bathroom, doing makeup before going out, everything became a public performance. Intimate privacy was paradoxically put on display for the world. It felt taboo and mesmerizing: an ordinary life ritualized into something meaningful simply because it was shared.

The genesis of digital intimacy

The web was originally supposed to be a realm of anonymity and escapism, yet it quickly transformed into a space for raw domestic reality as content. A young woman turned her bedroom into a stage and her routine into a ritual, inviting viewers into a space that was neither fully private nor fully public.

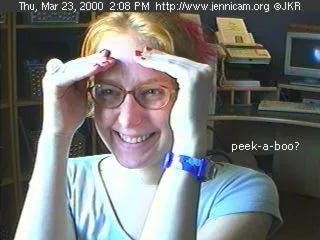

In 1996, 19-year-old Jennifer Ringley launched a site called JenniCam, where a webcam in her dorm room continuously snapped photos every few minutes and uploaded them to the web. There was no script, no filter, and no sense of privacy: Jenni’s dorm room became the world’s window into her day-to-day existence. It started as an experiment, but it struck a nerve. By the late ’90s, JenniCam was receiving millions of hits per day.

JenniCam wasn’t about glamour or scripted drama; it was about capturing the mundane in real time. Viewers were seeking an unfiltered look into someone else’s everyday life. This desire to witness ordinary life as it unfolded signaled a shift in how we perceived digital spaces: from escapist fantasy to ritualized presence.

Webcam as Ritual: a new kind of intimacy

Media scholar Ken Hillis, in his book Online a Lot of the Time, conceptualizes these webcam practices as rituals of visibility. According to Hillis, webcams merged communication as transmission (sending data) with communication as ritual (creating a shared experience). When Jenni turned on her camera each day, it wasn’t just a broadcast, it was an act of connection. Regular viewers began to structure their routines around her updates, creating a shared temporal zone: a ritual space where the mundane became meaningful.

The concept of the sign/body further complicates this relationship. Online, Jenni became a sign: a digital representation that simultaneously pointed to and stood in for her physical presence.

Viewers began to blur the line between the image of Jenni on their screen and the real person behind it, giving rise to a phenomenon Hillis calls telefetishism; the emotional attachment to the digital trace of a person rather than their actual presence.

As JenniCam grew, so did the tension between authenticity and performance. Ringley herself admitted that over time, her presence on camera felt increasingly performative, as if her own identity was being shaped by the gaze of her audience. Early webcam performers like Jenni were not only living their lives—they were curating them, knowingly or not, creating a new kind of digital self-performance.

From JenniCam to modern influencers

Fast forward to today, and the ritual persists: the mundane transformed into ritual, the private made public, the intimate commodified. Consider the countless TikTok and Instagram videos where young women film themselves lounging in their rooms, dancing in pajamas, or doing makeup. These digital rooms have become aesthetic symbols of intimacy and relatability. Even when creators hide their faces, or use pseudonyms, the sense of connection is still present.

Early webcam pioneers like JenniCam didn’t just anticipate influencer culture—they defined it. The bedroom performer remains a potent figure, largely thanks to the template those early webcam women created. They taught us that intimacy can be vicarious, and that authenticity can be curated. They made the mundane magical by treating it as worthy of attention.

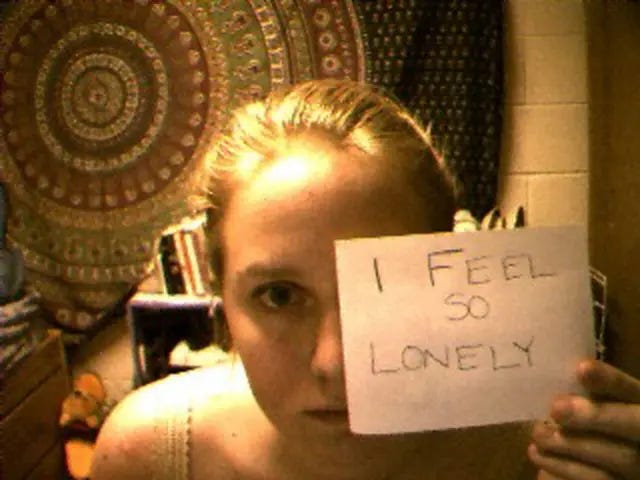

However, the question remains: Does this ritual of visibility actually bring us closer or simply give the illusion of closeness? Have we built genuine empathy through these shared rituals, or are we all, in a sense, alone together. Are we not connected through screens but isolated in reality?

The legacy of JenniCam suggests that even a fleeting digital trace of someone’s life can forge a real bond. It’s up to us to decide whether to embrace that bond as genuine connection or to view it critically as a carefully constructed illusion of intimacy.